By John McMahon

Travel Writer22 Aug 2019 - 6 Minute Read

Traditionally, 40 is a milestone birthday that weighs heavy. It’s usually a time for slowing down and taking stock of life, but that never occurred to me. Instead of a party at some chain restaurant, where acquaintances would prod me with joke gifts of canes and adult diapers, I was kayak-camping alone in northwestern Thailand.

Thailand has been my home for 13 years, and I spend as much time as possible kayaking its waters. When at home in Kanchanaburi, I kayak the River Kwai, made famous by the novel based on the railway bridge that spans it. During the rainy season, though, I head north to the densely forested mountains of Sangklaburi, where the rivers are flooded yearly by the monsoon.

Karen hilltribes populate the entire mountainous border between Thailand and Myanmar. Some have always been here, and some have come more recently as refugees fleeing economic and ethnic strife. Karen villages tend to be remote, difficult to access by vehicle, and usually on the banks of a river. Such is the case with Kong Mon Tha village, near where I planned to put in my kayak.

After hiking most of the night, I arrived at the village just after sunrise. When I got to the river’s edge, I found two local guys lounging by the water, enjoying an early drink of rice wine.

Karen people have their own language, but these two had worked construction in Bangkok, and so spoke Thai at about the same level as I. They asked what I was up to. When I explained to them about the travel kayak I had in my bag, and my plan to paddle downriver to the main road, they offered to take me further upstream. The river would be narrower, and thus the rapids bigger, and the paddling more challenging. They offered me a drink of their homemade wine while we spoke. When I asked how much money they wanted to guide me, they waved it off. “Nothing, we won't go far. Just for fun.”

I was beginning to doubt that my guides, whom I had met drinking grain alcohol at sunrise, really knew where we were.

By not far, I assumed a couple of miles, maybe – 45 minutes at most. An hour and a half later, I could still hear the river through the thick jungle to the left, but there had been no trail since we’d left the village. We were plodding waist-deep through a tea-colored bog that I wouldn't have dipped a toe in if it weren't for my guides, who took off their shoes and stepped in without hesitation.

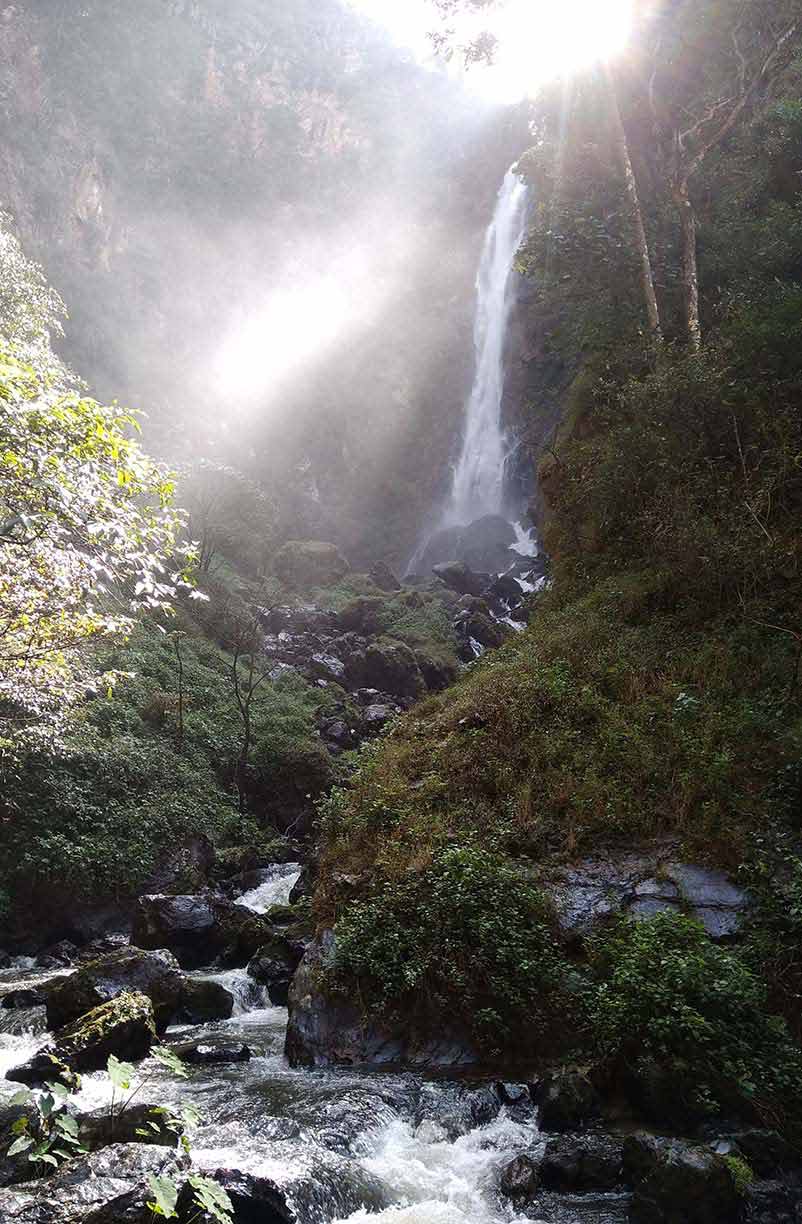

Covered in a thin layer of putrid ooze, we soon came to a small cascade, where we jumped in and bathed. There was no way around the waterfall – we would have to climb. It was only about 12ft (4m) high, but I was beginning to doubt that my guides, whom I had met drinking grain alcohol at sunrise, really knew where we were.

By then, my kayak bag was digging into my shoulders. I slung it off and handed it up the waterfall to one of my guides before climbing up myself. Instead of returning the heavy bag, my guide hefted it onto on his back, putting the shoulder strap around his forehead the way any natural mountaineer would carry a load.

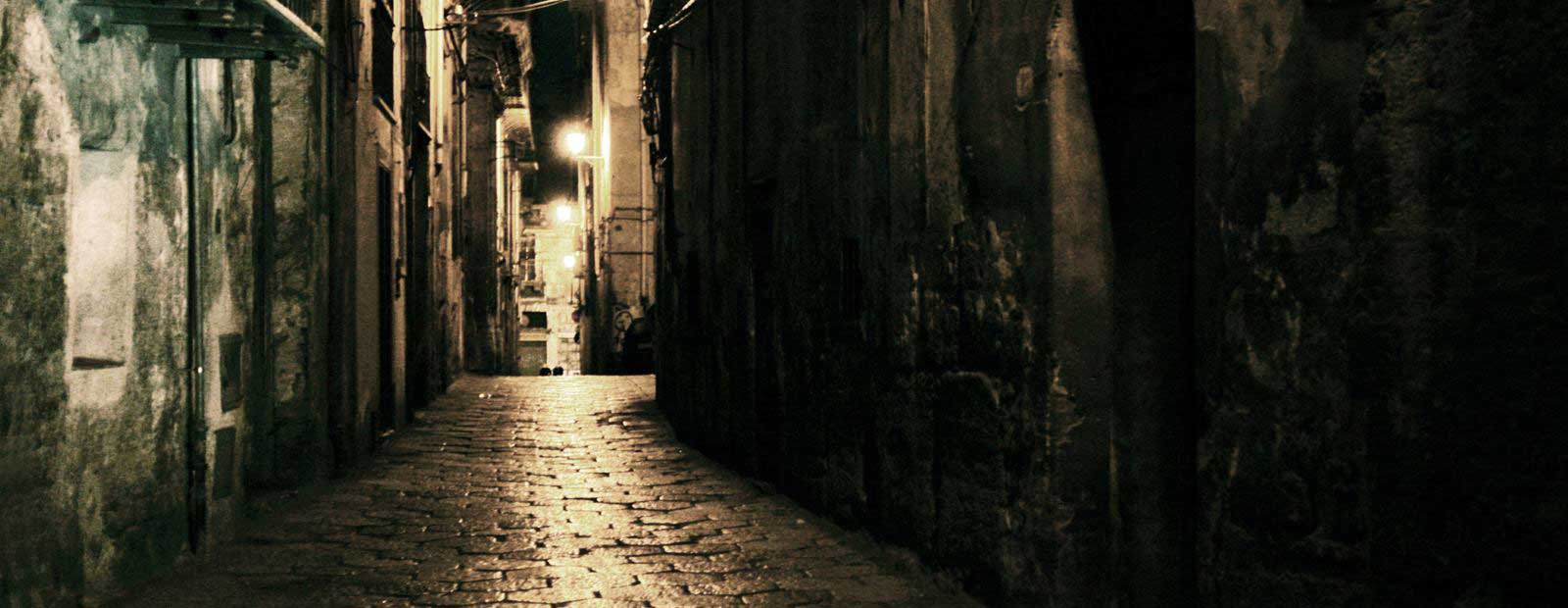

Another hour, and we were still pushing through dense jungle. Suddenly, the terrible realization that these young men had lured me into the wilds to rob me became clear as crystal.

They wouldn’t take any money when offered? And when I had asked how they were getting back to the village, they’d made vague references to a raft or a boat – did they mean my boat? I began to strategize and plan a defense. Getting away from them here would be useless, as they would track me down in no time; these hills and mountains were their backyard.

We continued our single-file march, with me continuing to scheme. The jungle opened unexpectedly onto a pineapple orchard, laid out in rough lines. My guides pointed to a bamboo hut on the far side of the field and said, “Our friend’s house,” before striding off ahead.

As I scanned the area, looking to make a break for it, one guide emerged from the hut, holding the kind of big, curved knife every Karen carries for cutting rattan. The other followed, holding aloft a couple of pineapples. They waved me over to the riverbank, where they sat on a flat rock and started to cut up the fruit.

“Pineapple is very good after a walk,” one of them said. The other nodded, smiling as he stuffed a juicy chunk into his mouth. As suddenly as my fears had arisen, they vanished. These men wished me no harm – they were happy to be out of the village, walking with a stranger, eating pineapple on the bank of a river under a blue sky dotted with fat white clouds.

The river water was cold and clear. From where I stood on the bank, I could see a never-ending series of white-topped waves crashing among great slabs of boulders. The Karens gave me their shoes to strap to the deck of my kayak. The “boats” they had talked about turned out to be two plastic jugs they would float on as they rode the rain-driven current back to their village.

I hung back in the water, watching as they rose up and over the six-foot waves. The cold water had erased any fatigue from the hike as I followed my guides to their village. They emerged from the torrent freezing, but grinning.

“You are strong swimmers,” I told them.

“I am, he cannot swim,” the taller of my guides said.

I looked at them aghast.

They nodded, still smiling, and with no more than a wave, walked up the path back to their village.

Discover similar stories in

fear

Travel Writer

John McMahon is a painter and writer. His work can be seen on platforms and in publications all across the English-speaking world.

1 Comment

Exciting Read!

This story connects very well to one of my travel adventures in South East Asia. The suspicions regarding strangers, the cloud of unknowing, the very fact that one never was sure one would get out of South East Asia alive.

I did though.

Your story was exciting, well written and I can relate to the feeling of going by boat or otherwise with pure strangers from another continent separate from one's ordinary reality in space but also in a sense of time.

Great Write!